Biodiversity and carbon credits in practice

A more practical dive into the connection between the voluntary biodiversity and carbon markets

Biodiversity and carbon are joint at every level: ecological, financial and political. That inevitably links the voluntary biodiversity market (VBM) and the voluntary carbon market (VCM) together. And although the post Global Biodiversity Framework biodiversity credit excitement faded, the biodiversity <> carbon topic is just as relevant. As reality sets in and market develops, we are moving from theory to practical implementation. It is time to go beyond a heavily simplified biodiversity credits vs carbon credits analysis and attempt to better define their overlap between these markets.

Let’s dive in.

How biodiversity and carbon credits work together now

There are multiple ways to think about it. Here is the way we do:

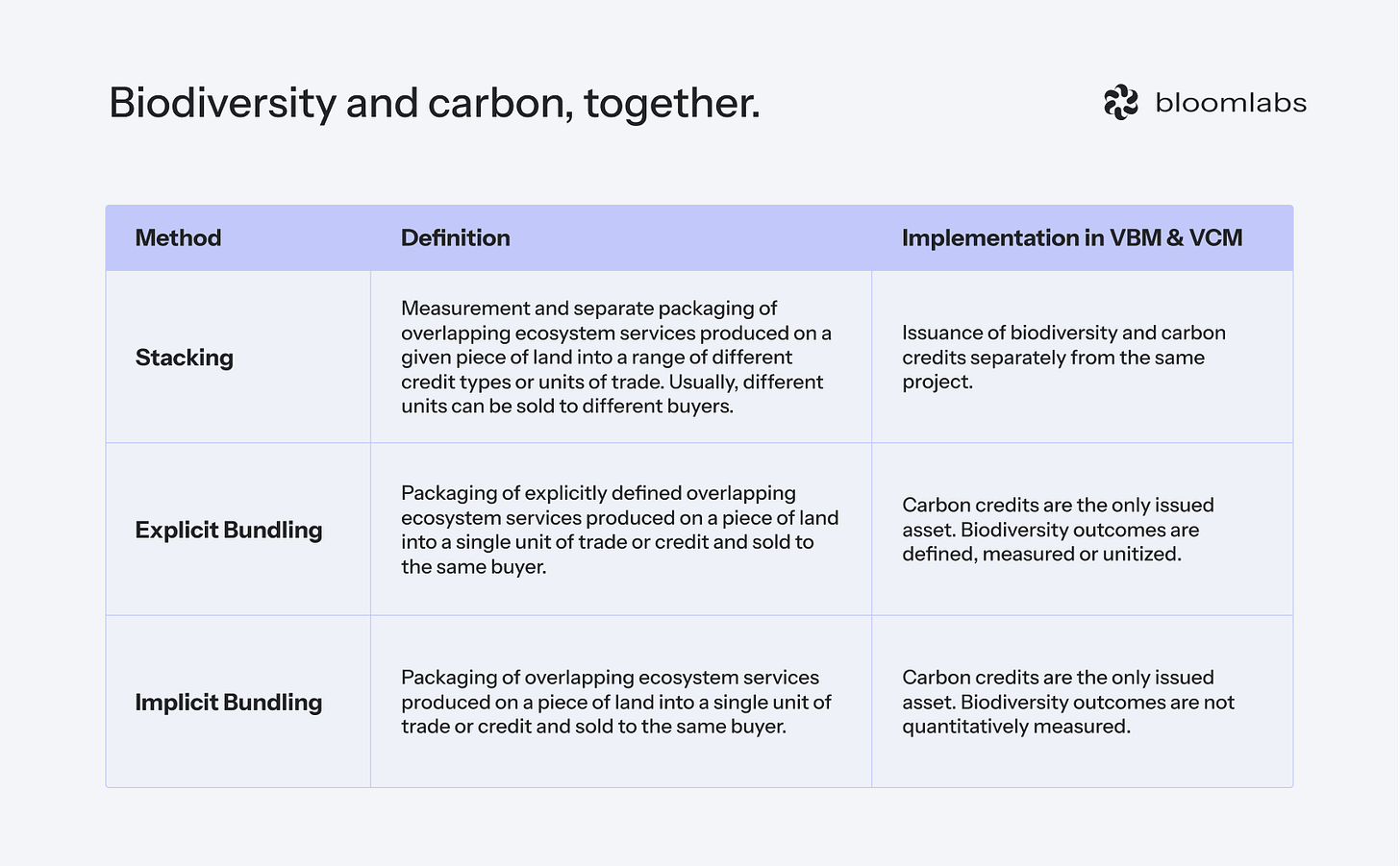

1. Stacking (same land, separate assets)

Issuing carbon and biodiversity credits separately from the same project is the most common way in which VBM and VCM connect. Such credits can then be sold to multiple buyers.

Benefits

Scale

Stacking biodiversity outcomes with carbon helps to use the existing carbon market infrastructure and reach scale faster than developing a separate biodiversity market.

Flexibility and higher revenue per unit of land

In theory, selling specific ecosystem services to specific buyers should lead to higher revenue per unit of land. If a developer can sell carbon outcomes to buyer X at $50/ha and biodiversity outcomes to buyer Y at $25/ha instead of selling a single or bundled credit for $60/ha to buyer Z, the seller would do it given that the transaction costs do not exceed $15/ha.

Better outcomes

The logic is that the explicit measurement of different ecosystem services leads to a more holistic land management focused on ecological integrity instead of optimizing for isolated outcomes.

Improved accounting of ecosystem services

The explicit measurement of different ecosystem services is expected to lead to better accounting for them.

Drawbacks

Additional complexity

The complexity is introduced at two levels: market and monitoring.

At the market level, outcome fragmentation, where different ecosystem services from the same land are sold to separate buyers who make separate claims, complicates environmental accounting. That makes mistakes and misuse, such as double counting, easier. Strict and well-defined credit usage criteria might prevent these risks but it would probably come with heavy additional transaction costs. So while stacking might lead to improved ecosystem service accounting through direct measurements, selling these services to different buyers might more than cancel this benefit out.

At the monitoring level, ecosystem unbundling is complex. Biodiversity science cannot yet support all of its use cases. We still struggle to reliably model how different ecosystem services interact, respond to interventions or change over time. These systems are non-linear, context-dependent and heavily influenced by variables we cannot fully measure or control. This uncertainty increases outcome delivery risk, especially when markets expect clear, quantifiable and isolated biodiversity metrics.

Additionality concerns

It can be difficult to prove that certain biodiversity outcomes have only been achieved because of the additional revenue from biodiversity credits and that carbon-only finance would not have achieved similar outcomes. The easiest cases to prove additionality are when additional interventions are required (e.g. native species reintroduction or invasive species removal) to achieve more significant biodiversity outcomes.

Additional costs

MRV and certification costs.

2. Bundling (same land, single asset)

In this case, carbon credits remain the only issued asset. Biodiversity remains a part of a carbon credit in two ways:

1. Explicit bundling (quantified biodiversity gains)

Here biodiversity outcomes are defined, measured or even unitized separately from carbon.

Benefits

Scale

Identical logic to stacking.

Higher revenue per unit of land

Although project developers cannot sell carbon and biodiversity outcomes to different buyers, they are able to prove to respective credit standards that carbon and biodiversity bundling (and the resulting higher revenue per unit of land) would allow them to achieve additional biodiversity outcomes.

Better outcomes

Identical logic to stacking.

Drawbacks

Less flexibility

Unlike stacking, explicit bundling does not offer the flexibility of selling different credits to different buyers.

Additional complexity

Similar to stacking, explicit bundling introduces more complexity. It mostly lies in biodiversity monitoring (and not the market level) since biodiversity outcomes need to be additionally measured.

Additionality concerns

Any combination of environmental credits represents additionality concerns. However, they are less significant for explicit bundling since separate environmental assets are not issued.

Additional costs

MRV and certification costs.

2. Implicit bundling (implied biodiversity benefits)

Here, biodiversity is not quantitatively measured. It is the co-benefit approach, popularized by the CCB (Climate, Community and Biodiversity) Standards, managed by Verra - a key standard both in VCM and VBM. More recently, the approach has been reinforced by Equitable Earth (formerly ERS). This modern carbon standard has directly embedded biodiversity into their methodologies and plan to measure it quantitatively as soon as there is more consensus on biodiversity metrics and measurement costs go down.

Although there is no official definition of what a voluntary biodiversity market is yet, biodiversity-focused finance from implicit bundling is usually not considered as part of it.

Benefits

Ease of implementation

Compared to quantifying biodiversity, following a qualitative theory of change or certain guardrails to ensure no biodiversity loss in carbon projects is easier. That is why in recent years, the CCB co-benefit label has become the default for nature-based carbon projects to signal high quality.

Better outcomes

Identical logic as above with natural limits of not measuring all these outcomes.

Drawbacks

No quantified outcomes

Undefined outcomes cannot achieve their true value.

Over-reliance on carbon credits

Under the co-benefit scenario, biodiversity gain is completely dependent on carbon credits. This excludes landscapes that are not eligible for carbon credits.

Additional costs

MRV and certification costs.

Stapling and nesting

Beyond stacking and bundling, two more methods of combining biodiversity and carbon are being developed: credit stapling and nesting.

Credit stapling is the sale of different types of environmental credits (e.g. carbon and biodiversity) from different projects to the same buyer.

Credit nesting is the hierarchical nesting of environmental claims from higher-order to lower-order. The highest-order claim focuses on ecosystem integrity and targets holistic ecosystem recovery. It is followed by the community/habitat claim focused on enhancements within specific communities or habitats. It contributes to biodiversity without necessarily impacting full ecosystem resilience. Finally, the lowest-order claim is species-specific and targets specific biodiversity gains in target species without necessarily focusing on the ecosystem-level impact. CreditNature, the creator of the concept, has written more about it here.

Both methods are promising and stapling already has been successfully tested (see more below). They fall out of scope this time.

Present state

As of 18 December 2025, here is the overlap between VCM and VBM in numbers, powered by Bloom, our market intelligence platform:

Organizations

From 1,106 VBM organizations, 359 explicitly operate in VCM. A significant portion of the remaining organizations such as consultants, policymakers or NGOs are also linked to VCM. Hence, we estimate that at least 50% originate in carbon markets.

Once you serve a single environmental market, entering adjacent ones is a natural next step, especially for credit schemes, project developers and consultants.

Schemes

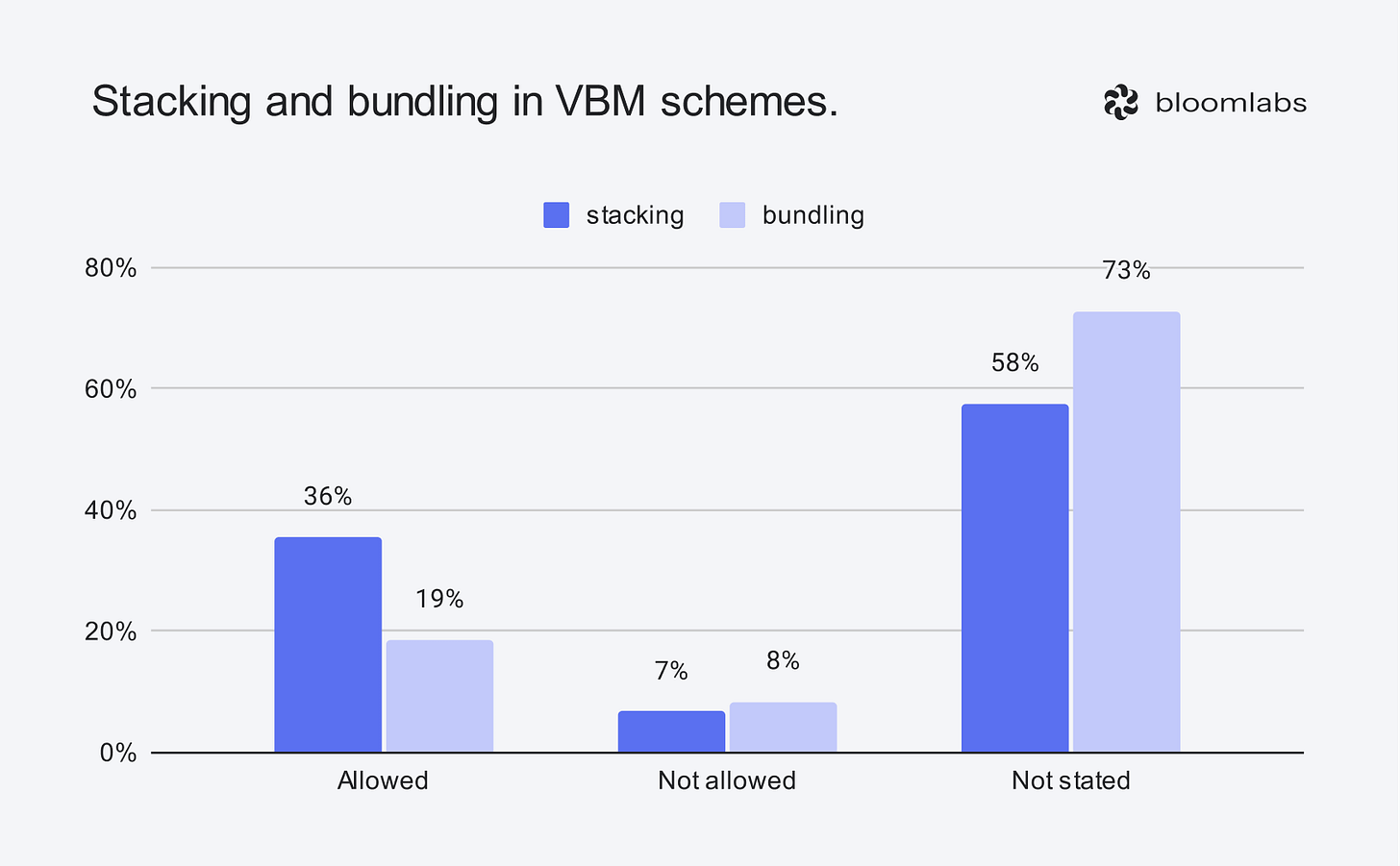

While most credit schemes do not yet state their credit stacking and bundling policies, some early trends are visible.

Out of 59 schemes covered, 21 explicitly support stacking. Out of them, 9 also support bundling and the rest either provide no information or do not support it. 11 schemes support bundling. Out of them, 9 also support stacking and the rest provide no information.

Projects

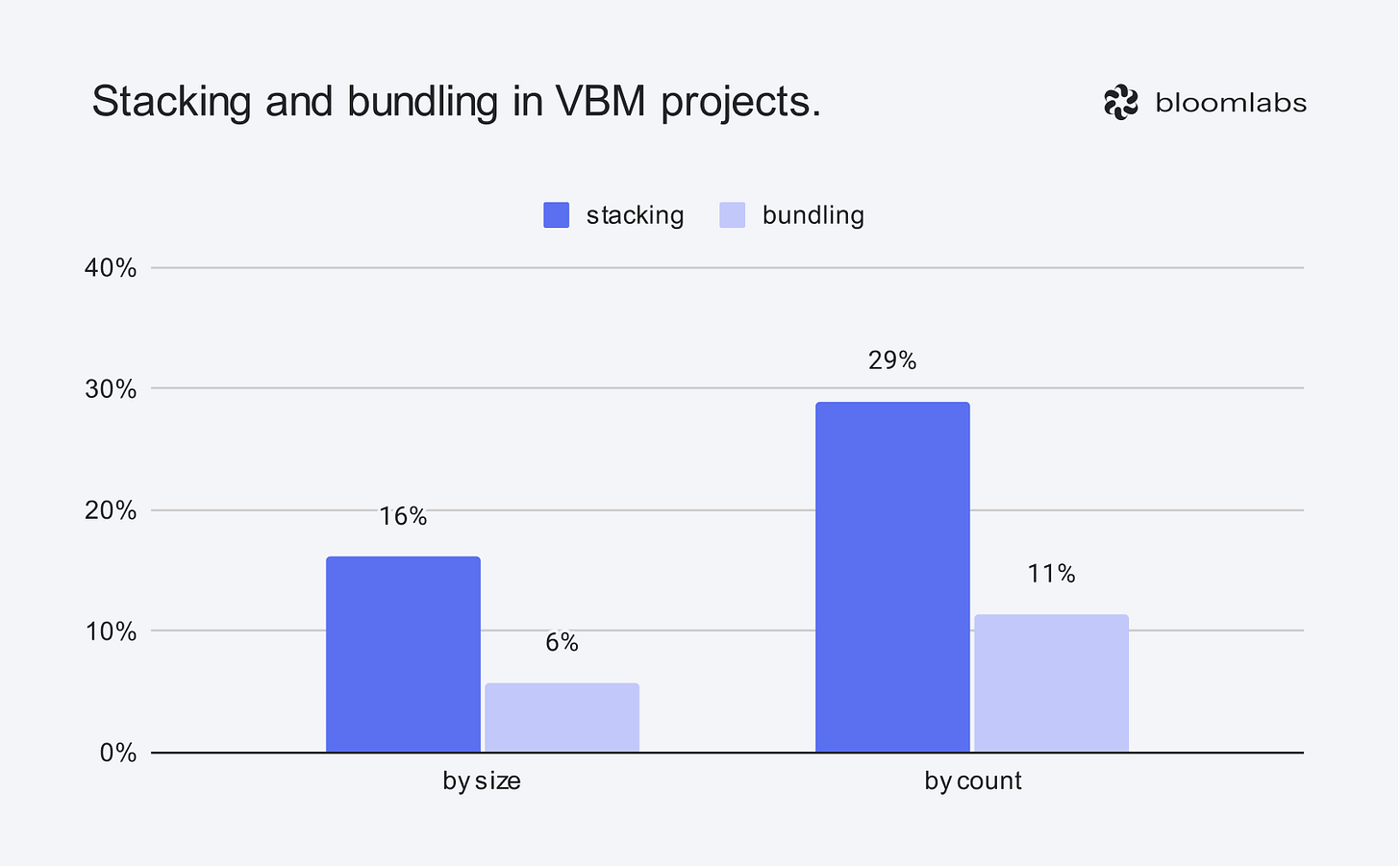

42 projects support stacking with only 15 of them also supporting bundling. 16 projects support bundling with 15 of them supporting stacking as well. 23 biodiversity credit projects explicitly do not support stacking and 52 do not support bundling. The remaining (74 out of 146) projects do not report their stacking and bundling policies.

Projects that support stacking cover roughly 866,790ha while projects that support bundling cover about 320,350ha - respectively about 16% and 6% of the total area covered across all projects. The average project size when carbon stacking and bundling is used is around 20,640ha and 20,000ha, respectively, similar to the average nature-based carbon project size.

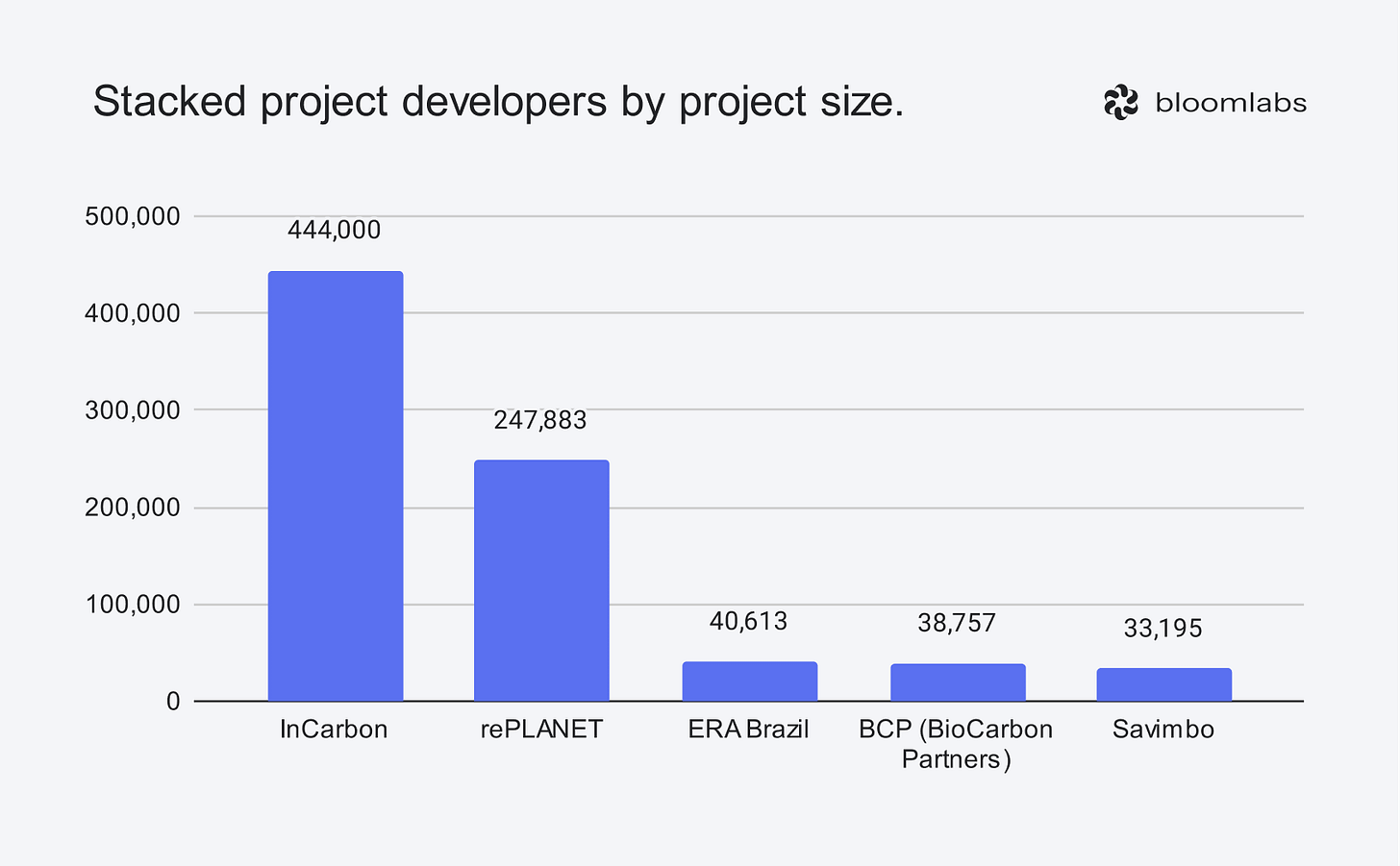

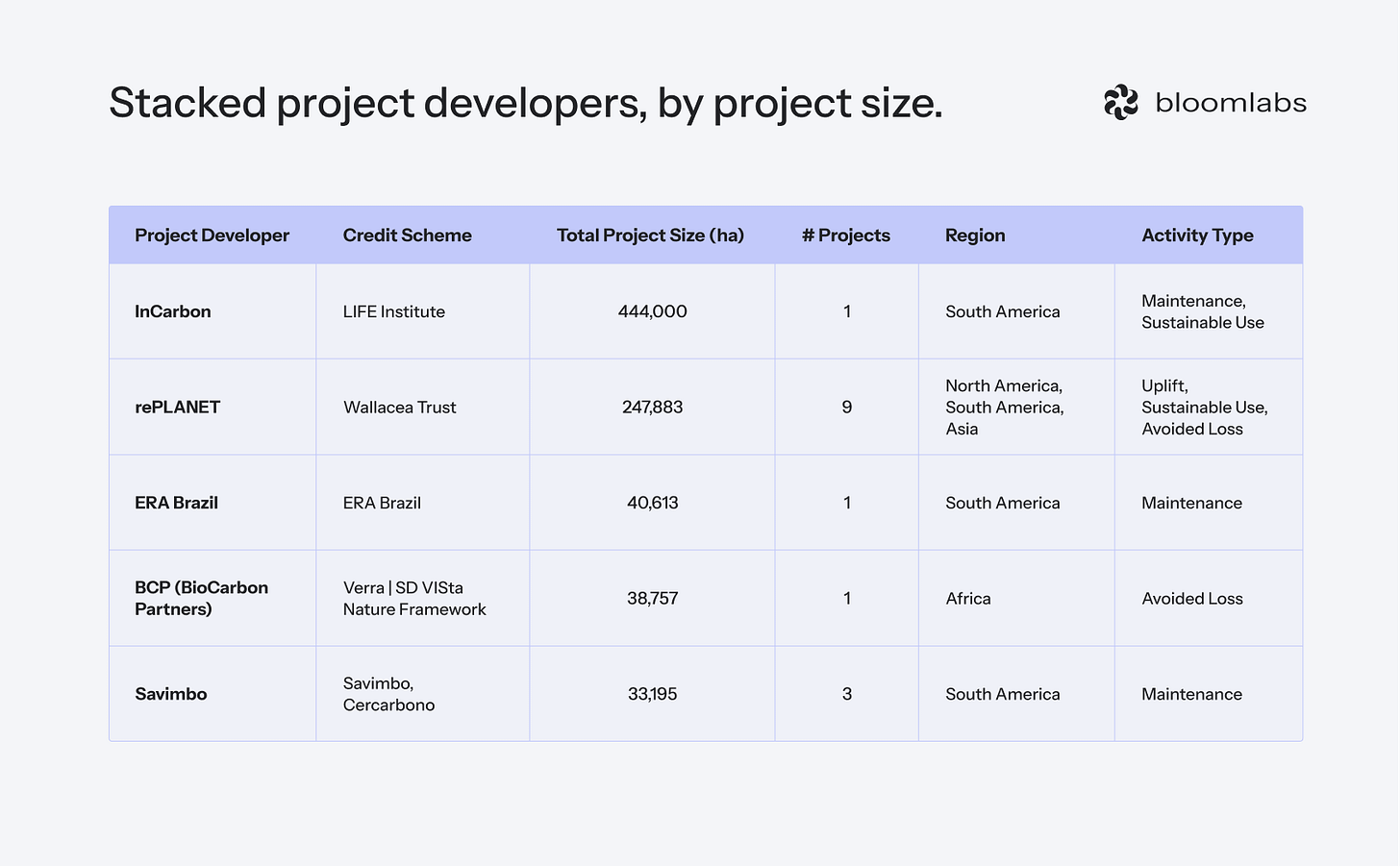

The projects that support stacking are dominated by 5 project developers: InCarbon, rePLANET, Savimbo, ERA Brazil and BCP (BioCarbon Partners). Together, they manage about 804,450ha, making up 92.8% of the total area for stackable projects.

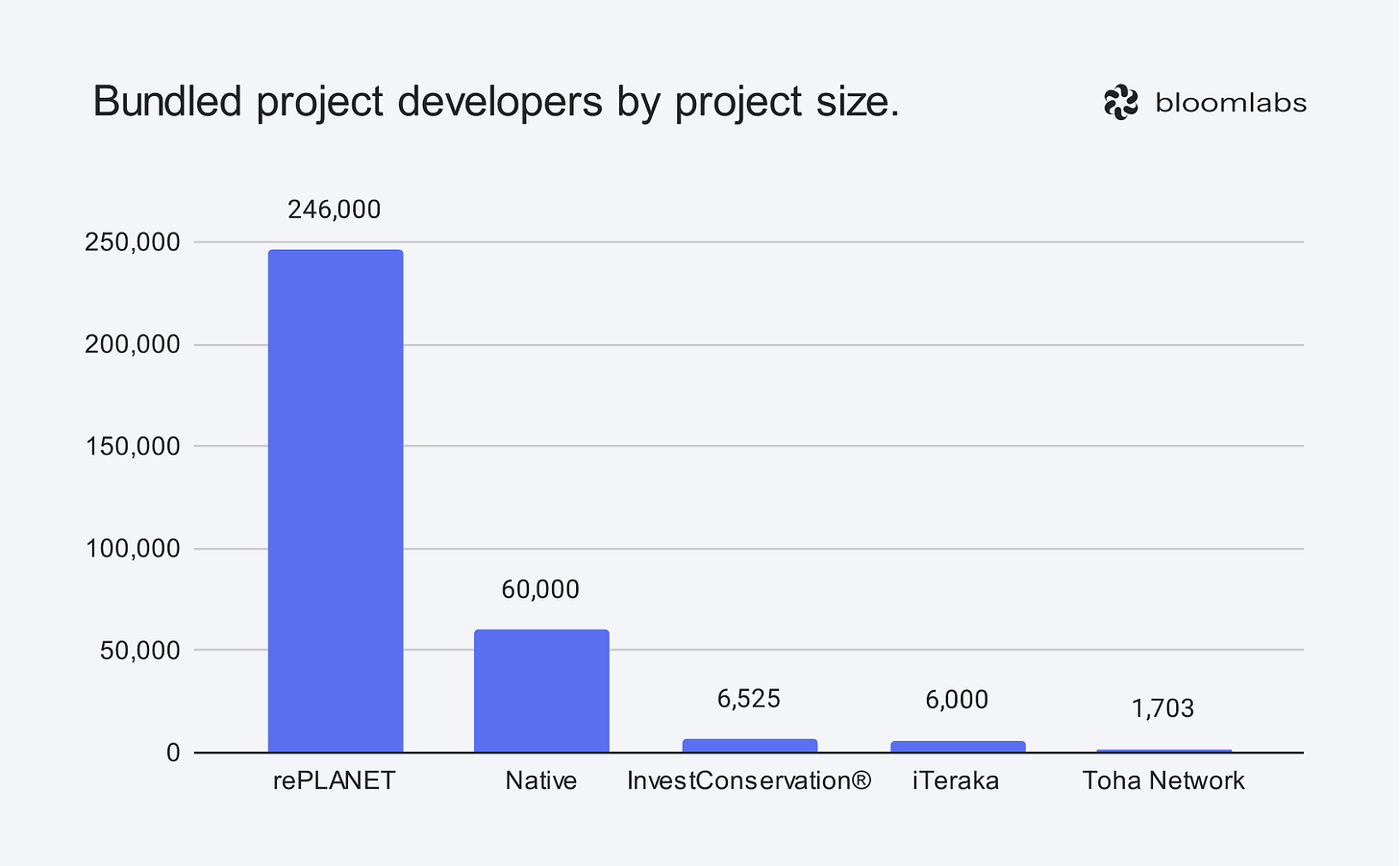

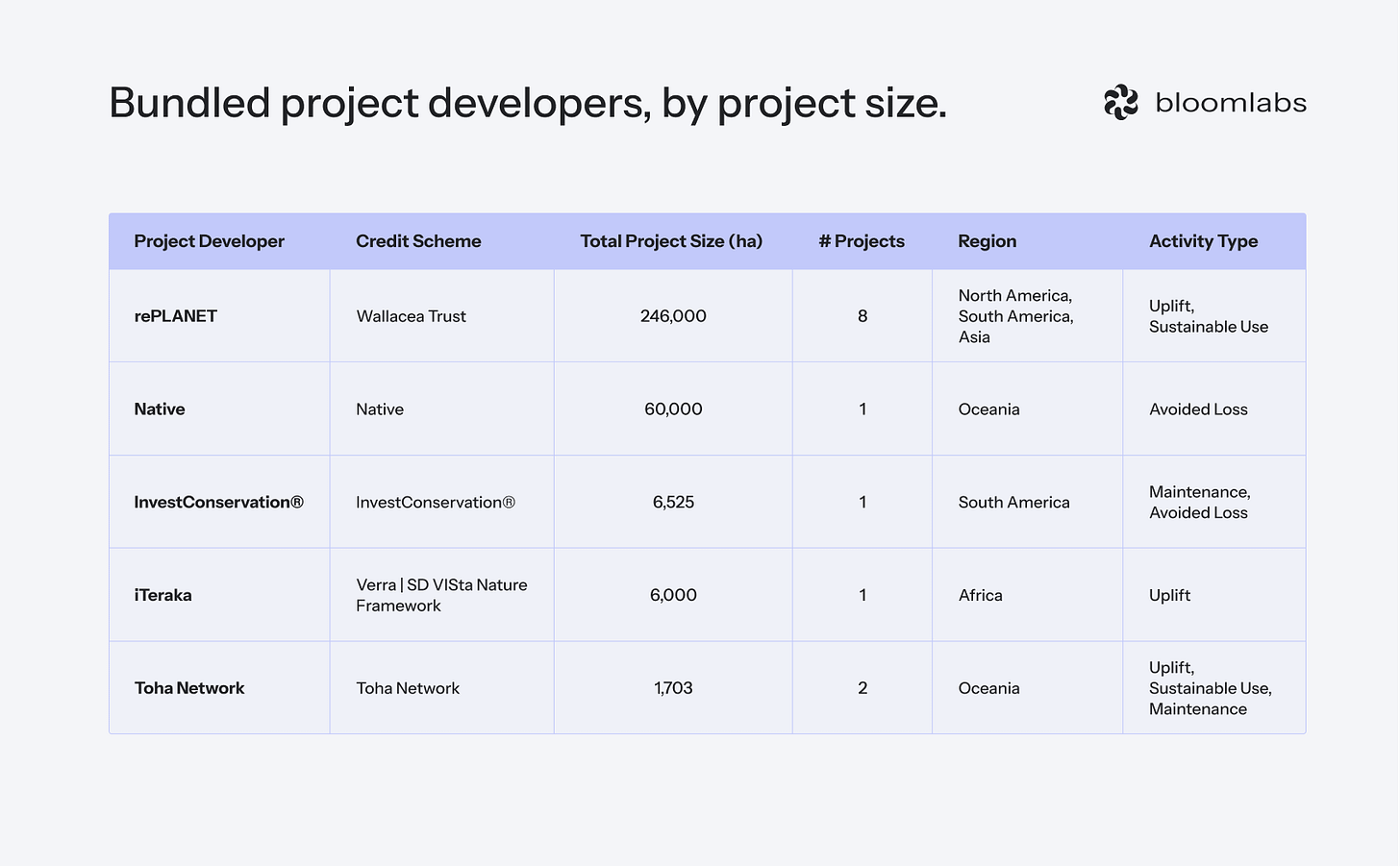

The projects that support bundling are once again led by rePLANET. They alone make up more than 76% of the total area for bundling-friendly projects with 246,000ha. The remaining 4 project developers cover the rest of the market.

As we can see, the stacking and bundling-friendly supply is still very thin and is controlled by rePLANET.

It is also important to note that stacking and bundling can be either freely combined with any 3rd party carbon standard or permitted only with the respective carbon standard under the same organization (e.g. Plan Vivo’s PV Nature allows stacking only with their own PV Climate and Verra’s SD VISta Nature Framework allows stacking only with their own VCS Program). Wallacea Trust, Cercarbono and CreditNature are notable credit schemes that allow combining biodiversity credits with any other carbon standard.

Transactions

So far, 5 suppliers lead biodiversity credit transactions connected to carbon:

Wilderlands. They have partnered with carbon project developer Tasman Environmental Markets (TEM) to sell their credits to the same buyer. TEM’s carbon project is in Papua New Guinea while Wilderlands’ biodiversity project is in Australia. Such a transaction is the above-mentioned credit stapling.

Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari. The NGO used Ekos’ BioCredita Programme to sell biodiversity credits stapled with carbon credits - another example of credit stapling.

Savimbo. Their biodiversity credit sales are often bundled with carbon credits, water credits and tree planting.

Nat5. They have facilitated a biodiversity, water, and carbon credit pre-purchase by a Mexican investment firm. The exact amount earmarked for biodiversity is unclear but the bulk or all of it should go there.

InvestConservation®. Their biodiversity unit is directly tied to carbon sequestration.

Additionally, rePLANET reported to have secured an investment for most of their bundled and stacked carbon and biodiversity credit projects mentioned earlier.

And finally, Ponterra has recently made news by securing a first-of-a-kind $270,000 biodiversity-credit backed loan for their carbon restoration project. It is an innovative transaction that is not a traditional credit sale and deserves further analysis in the future.

It is difficult to estimate the total size of these transactions (since many are bundled into a single price) but it is unlikely to be above 20% of total VBM sales of ~$10-15 million.

Why is stacking more popular than explicit bundling in VBM?

True stacking is non-existent in most of the largest nature markets, such as the US-based compliance wetland and stream market or the species mitigation market. One key exception is England’s Biodiversity Net Gain. It is also widely accepted to be the riskiest way to combine ecosystem services. Yet, as mentioned, stacking (29%) is almost 3 times more common than explicit bundling (11%) in VBM. It is worth going beyond our attempt to rationalize why in the previous article.

Sales flexibility and revenue maximization

Since true stacking allows selling different ecosystem services (or credits) to different buyers, a developer could technically sell each ecosystem service to the most interested buyer and earn higher revenue per unit of land compared to bundled credits. In most cases, bundled credits are purchased because of a single ecosystem service/credit in the bundle. The rest are “co-benefits”, bound to be valued less.

Important note: we have not seen strong evidence of stacking leading to higher revenues in other nature markets yet.

Narrow buyer mandates

Most buyers procure credits one credit type at a time, in line with their sustainability strategies and legal obligations (e.g. carbon only, biodiversity net gain/offsets only, nutrient only, etc.). That is why they prefer to buy the specific credit they are required to report on and not a package that includes other ecosystem services. Biodiversity is gaining importance in corporate reporting but biodiversity credits are not part of any such corporate reporting mandates yet. Hence, they remain an afterthought.

That is why so many hope that the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) and Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) do to biodiversity markets what the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) are doing to carbon markets. That would create, ideally together with corresponding regulations, a defined reason for corporates to buy biodiversity credits.

Price discovery and product differentiation

Separate biodiversity and carbon credits make it easier to benchmark prices, compare standards and run tenders. In contrast, bundled products are harder to value and compare because the contribution of each service to the price is often unclear. rePLANET and their bundled credit pricing struggles is a great example.

In other words: stacking matches regulation, corporate accounting and procurement practices better than bundling. Different markets are built for different outcomes and prefer to be considered separately, even if the outcomes are from the same land.

The big question is whether biodiversity and carbon credits will be sold to separate buyers. If that is the case, then stacking really makes sense.

So far, it is too early to tell but we do see a couple of important variables for the “different buyer” scenario to materialize:

Different claims. Carbon credits support offsetting claims while biodiversity credits support contribution claims. It can lead to different credit purchases or might even reinforce one another.

The overlap between emitters and companies responsible for biodiversity loss. It is significant but not complete.

Disclosure pressures and regulations. SBTN and TNFD mirror SBTi and TCFD but are still early and do not consolidate into a single framework. The same is true for regulations. The result: no single process to procure both carbon and biodiversity credits.

Buyer’s ability to accept multi-credit complexity. So far, we see a push toward simplicity, not complexity.

The shadow voluntary biodiversity market

We often say that the “shadow” VBM is significantly bigger than the standalone market, which, according to our data at Bloom, likely stands at $10-15 million in total sales. The shadow VBM is the total financial value attributed to biodiversity in other voluntary nature market transactions besides VBM itself, primarily VCM. In effect, it is a combination of implicit and explicit bundling.

To prove that, let’s look at a couple of data points:

Case study 1: rePLANET

Carbon and biodiversity credit project developer rePLANET specializes in explicit bundling and stacking. rePLANET is closely linked to the popular “basket of metrics” Wallacea Trust biodiversity credit methodology since the company’s CEO, Dr. Tim Coles, is also the founder of the research non-profit group Operation Wallacea, the organization behind Wallacea Trust. rePLANET likely has the biggest project pipeline in the market of at least 11 projects that span almost 250,000 hectares and are forecasted to generate ~3.04 million credits and 10.6 million biodiversity units of gain over the next 20-30 years.

Surprisingly, the units of biodiversity gain and not credits are most important to rePLANET. They are quantified exactly the same way as credits using the Wallacea Trust methodology. However, they are not issued as separate assets and hence are not required to follow the established credit issuance practices, such as keeping a ~20% permanence reversal buffer. Instead, they are simply bundled with carbon credits - either completely or up to a certain point (e.g. 50% uplift). Any uplift beyond 50% can be issued as separate biodiversity credits, which becomes stacking.

Although rePLANET has not announced any official transactions of these bundled and stacked projects yet, it claims to have received funding for multiple such projects and real interest from key carbon investors and buyers. According to rePLANET, these unitized biodiversity gains is one of the key reasons why their carbon projects gain attention (next to their 60%+ benefit sharing policy) and achieve the “biodiversity premium” in credit pricing. The company estimates that such units of biodiversity gain are much larger than VBM.

Case study 2: biometrio.earth

biometrio.earth is a biodiversity MRV company that combines remote sensing, acoustic and imaging data. Their team has exceptional biodiversity MRV expertise, having managed the monitoring of Mexico’s Aichi Targets across the whole country.

Their key market now? VCM. Not VBM. They have identified the need for carbon project developers to quantify biodiversity gains in their project area even if they are not required to do so, going beyond the qualitative (e.g. CCB) labels. Chirping birds or a shy tapir passing by is a source of beautiful promotional material both for project developers and credit buyers. And although not unitized, it is also a quantitative proof of biodiversity outcomes.

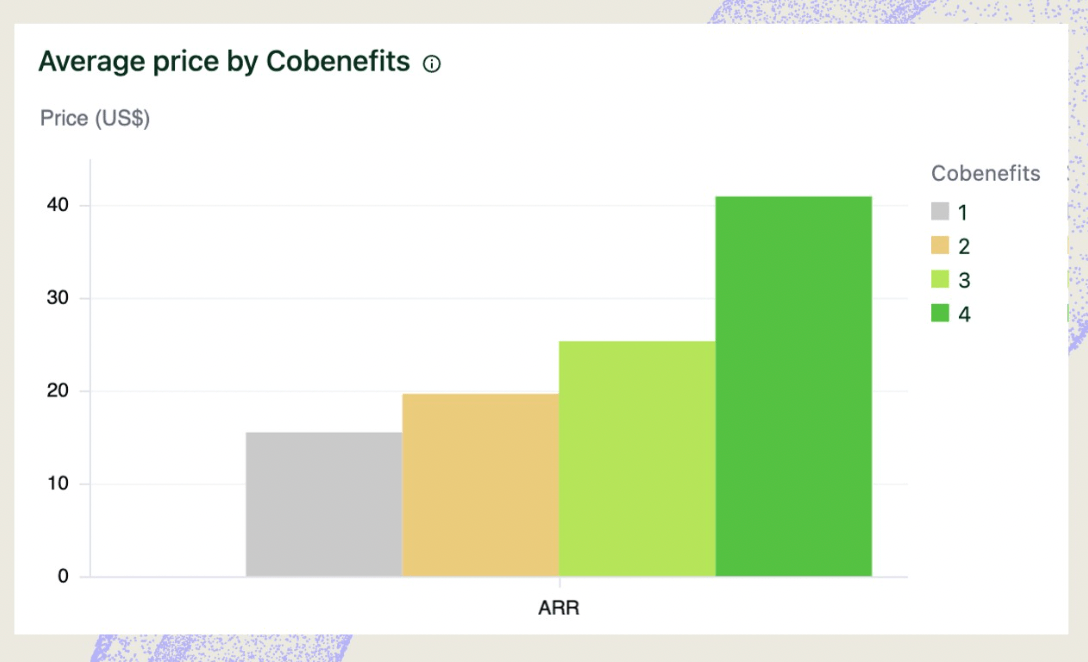

The increasing importance of co-benefits in carbon

AlliedOffsets and Sylvera have recently illustrated the importance of carbon credit co-benefits (or implicit bundling) in numbers. Using AlliedOffsets’ data and Sylvera’s project ratings, they identified two key drivers of price premiums: quality (i.e. their own ratings) and co-benefits (i.e. social, biodiversity and community value beyond only carbon). For example, ARR (Afforestation, Reforestation, and Revegetation) credits with co-benefit score of 4 average a price of $40.18, while a co-benefit score of 1 is at $15.49.

Such carbon credit transactions with co-benefits are becoming more common as well:

In 2023, the share of VCM transactions from projects with co-benefit certifications grew to 28%, up from 22% in 2022, fetching an average price premium of 37%. Nature-based carbon reduction and removal projects that have potential for environmental and biodiversity co-benefits display a similar market trend. This is particularly true for afforestation, reforestation and revegetation (ARR), and improved forest management (IFM) projects. Between 2022 and 2023, prices for ARR and IFM credits rose 31% and 11%, respectively. - Optimizing for Biodiversity in the Voluntary Carbon Market | JPMorganChase and Carbon Direct

Final verdict

According to Ecosystem Marketplace, the cumulative voluntary carbon market from 2021 to 2024 is estimated at around $5.3 billion and Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) carbon credit category comprises at least $750 million of it in 2023 and 2024 alone. On top of that, the nature-based carbon offtake agreements are rapidly growing, valued at at least $450 million in 2024. If these offtakes materialize and biodiversity represents even 5% of the total value, that already makes it about two times larger than the standalone VBM.

Competition between the two

The markets compete across the following axes:

1. Project design

Projects must usually balance maximizing carbon gains with maximizing biodiversity benefits, introducing trade-offs. Maximizing carbon sequestration can lead to non-native high-density monocultures (often dominated by eucalypt, pine and acacia species) which usually hurts biodiversity in the long-run.

On the other hand, maximizing biodiversity is likely to result in near optimal carbon outcomes. The challenge? These carbon outcomes usually occur outside carbon crediting periods (up to 40 years) and are less predictable.

Because native-species and mosaic approaches often have less predictable carbon curves and may generate fewer credits within project crediting periods, they can be less attractive to carbon-focused investors and developers compared to plantations with commercial species. - Optimizing for Biodiversity in the Voluntary Carbon Market | JPMorganChase and Carbon Direct

What is good for carbon is not always good for biodiversity. The opposite is usually true given a long enough timeframe.

2. Demand

So far, it seems that the buyer overlap between the two markets will be significant.

As mentioned earlier, buyers usually procure credits one credit type at a time. And while carbon credit procurement exists, biodiversity credit procurement does not. That incentivizes carbon credit buyers to address the rising pressure to focus on biodiversity by shooting two birds with one stone - buying carbon credits with biodiversity co-benefits. On top of that, the recent carbon market scrutiny pulls every other voluntary environmental market, including VBM, back by concentrating carbon sellers and buyers on “fixing carbon first”.

3. Supply

While VCM is limited to natural carbon sinks, VBM applies to virtually every natural and productive ecosystem. This results in both markets targeting overlapping ecosystems like forests or wetlands. There project developers often must choose between prioritizing carbon or biodiversity outcomes. This can introduce additionality challenges if the same actions generate similar carbon and biodiversity outcomes.

Biggest risk for biodiversity credits

Since both VCM and VBM is a buyer’s market, the key risk for VBM is big buyers settling for carbon credits based on qualitative co-benefits without even considering standalone biodiversity credits in their procurement process. In other words: implicit bundling.

Is there a silver lining?

Can different carbon and biodiversity outcome time horizons be combined? One solution is to align time horizons by extending carbon crediting periods. Going beyond already multi-generational commitments can be difficult though. Another solution is to adjust project interventions:

In addition, projects that mimic natural succession—with fast-growing species dominating the early years of the project and a more diverse selection of slower-growing species planted underneath—have the potential to provide rapid carbon accumulation initially while facilitating the transition to a more biodiverse state as the project matures. Some ARR and uneven-aged-stand IFM projects already have a precedent of mimicking natural succession and integrating Indigenous knowledge to support local communities while promoting biodiversity. Over time, species-rich forests and ecosystems generally store more carbon than less diverse environments due to more efficient and complementary use of resources. - Optimizing for Biodiversity in the Voluntary Carbon Market | JPMorganChase and Carbon Direct

Should VBM even exist?

So far, the case for standalone biodiversity credits can seem weak. Carbon credits are more established, more fungible, tradable, have a clearer business case and, most importantly, often already address biodiversity indirectly. A new credit type introduces more fragmentation in an already divided market, which will inevitably increase transaction costs and add a heavier load on the buyers.

One simple fact we have been alluding to justifies the existence of voluntary biodiversity credits though: many ecosystems do not sequester or store enough carbon to be financed by carbon credits alone. Not all ecosystems are carbon sinks. Inland freshwater ecosystems (i.e. rivers, streams and lakes), coral reefs, fire-prone savannas and grasslands are some such examples. In fact, even the ecosystems that are seemingly perfect for carbon credits (e.g. peatlands) often cannot be financed with carbon credits alone if they are not large enough or do not avoid enough carbon emissions. And of course, carbon is never the only ecosystem service that matters and is forced to act as a proxy for so many others (e.g. water, biodiversity, pollination, etc.) under the current funding system. One thing is certain: we should better understand which ecosystems fit which market better and what exactly the overlap is.

Beyond different supply, biodiversity credit projects are more local, support different claims, are less tradable and can target ecosystem services that buyers rely on, such as water, more directly. That leads to even stronger project finance dynamics than in carbon markets, where a single buyer is often responsible for funding a significant part of the project. It also leads to different demand drivers from VCM: supply chain risk management and, to an extent, insetting instead of general claims. Importantly, these demand drivers are more internal to the “buyer“ and do not have to be based on tradable market instruments - something we plan to explore more in the future. No biodiversity credit methodology has been designed specifically for these use cases so far but we expect that to change.

The role of policy

Biodiversity credit mechanisms are progressing not only in the non-jurisdictional voluntary markets. A growing number of countries are exploring utilizing them either at a voluntary or compliance level. The recent report by the International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity Credits (IAPB) analyzes 19 government-led nature credit frameworks with more in the pipeline. Since natural resources are often public goods, most market participants are pinning their hopes on governments to build these markets by incentivizing demand, setting rules or even buying credits themselves.

EU Nature Credits Roadmap

The recently announced 2-year roadmap is arguably the most important nature market policy development in 2025. The Commission is well aware of the need to align the roadmap with their EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) Regulation.

First of all, CRCF already uses implicit bundling with biodiversity by requiring carbon farming activities to “generate co-benefits for biodiversity and ecosystem services”.

Their argument for standalone nature credits is also similar: some ecosystems cannot be funded via carbon alone and that is where nature credits come in.

Nature credits can also cover a broader scope, as they can apply to interventions and areas non-linked or with limited additional carbon sequestration potential but high biodiversity value, such as supporting pollinators or restoring dry ecosystems.

While the Commission claims not to have plans beyond 2027, they are being asked for the same things every other government that runs nature credit markets is asked: clear rules and clear demand. It will be interesting to see how the EU will allocate resources between carbon and nature credits as some organizations push for the carbon credits to be the primary mechanism with nature credits complementing it.

Historically, compliance nature markets and carbon markets were separate. Now, the gap is closing with the EU and Australia being great examples.

Future scenarios

We see four scenarios of how biodiversity and carbon markets will interact.

1. VBM becomes largely separate

VCM continues to further integrate biodiversity but the non-overlapping ecosystems, different use cases and claims push VBM to become a standalone market.

2. Bundling: biodiversity remains qualitatively and quantitatively embedded in VCM

The implicit and explicit bundling scenario. As mentioned earlier, implicit bundling arguably the biggest risk for the voluntary biodiversity market.

We have quoted the recent brilliant paper on biodiversity in VCM by JPMorganChase (biggest bank in the US) and Carbon Direct (one of the most respected carbon management firms) extensively so far. There, the authors explicitly refused to analyze voluntary biodiversity credits, “opine on the issuance of stacked carbon and biodiversity credits for a unique project” or “address the validity of biodiversity credits as fungible units for nature-positive claims or mitigation”. The paper also said that “the market (VCM) lacks a clear signal from buyers that quantifiable and meaningful biodiversity outcomes are a priority on par with carbon. This is compounded by a lack of clarity on what constitutes a high-quality project in terms of both biodiversity and carbon.”.

We see two ways to interpret that:

Demand side VCM participants want to focus on one market at a time, following the “let’s fix carbon first” logic.

Demand side VCM participants are skeptical about biodiversity credits altogether.

3. Stacking: separate biodiversity credits exist but are mostly stacked to carbon

The current trend grows and project developers issue both credit types from the same land. Although separate, biodiversity credits remain tied to carbon markets.

4. A standalone non-credit biodiversity market is established

A non-credit biodiversity market takes hold to become a “risk-free” way to measurably contribute to biodiversity. Non-credit biodiversity certifications such as The Global Biodiversity Standard (TGBS) or Accounting for Nature (AfN), together Wallacea Trust, become the standard methods to prove biodiversity outcomes for any conservation project, whether based on credits or not. A meaningful number of quantified biodiversity projects are already privately funded without credits. For example, 3Bee is piloting over 100 such biodiversity projects in Europe.

Which scenario is the likeliest?

These scenarios are not mutually exclusive. Actually, we see all four becoming much larger. The question is not necessarily which scenario will happen but in which order they will play out. Here is one possible sequence:

Bundling and stacking grows

Functional VCM rails and the growing future demand of high-quality carbon credits provide more certainty than the standalone voluntary biodiversity market. In this phase, the shadow VBM becomes proportionally even larger with explicit unitized bundling and stacking taking over the currently dominant implicit bundling. Bundled and stacked biodiversity credits become the quality assurance layer for carbon credits.

Project-based biodiversity credit finance is validated

More VBM-specific demand drivers such as supply chain risk management and insetting together with contribution claims become more common. Some key large projects are funded and sold, setting a precedent for more projects, often co-developed with buyers. Corporate biodiversity credits become a more common industry term.

Standalone VBM takes shape

Crediting standards consolidate, claims and units become clearer, the market receives (inter)national policy support, TNFD and SBTN integrate with biodiversity credits.

This sequence is coupled with a consistent growth of non-credit biodiversity projects driven by philanthropy, marketing and supply chain management.

Beyond the initial competition, we believe VCM will become the gateway drug to standalone VBM, roughly following the “biodiversity co-benefit story → separate biodiversity KPIs with monitoring → carbon credits bundled and stacked with biodiversity credits → standalone biodiversity credits” logic as the market matures, supporting policy develops and reporting pressures grow.

A big step in validating true standalone voluntary biodiversity credit demand will be the credit issuance of established carbon standards like Verra and Plan Vivo who will join Cercarbono, the only ICROA-certified standard to have issued credits so far. Since all support stacking, this will also be an important test of how attractive combining these credits with nature-based carbon is to buyers.

Key themes

The biodiversity <> carbon space is still early and lacks evidence for a confident numbers-based analysis. Having said that, we see a couple of key themes:

Nature markets must stick together

Ecosystem Marketplace reports that $347.2 million worth of nature-based (AFOLU) carbon credits were traded in 2024. Internally, we have just verified over $10 million in total voluntary biodiversity credit sales over the past 3 years. AI startups regularly raise more money in a single round than both of these numbers put together. In the grand scheme of things, VCM and VBM are two drops in the ocean. Nature markets must stick together, even if there is some competition between the same supply and, more importantly, demand.

Biodiversity credits = quality assurance layer for carbon credits

Nature-based carbon credits with quantified biodiversity outcomes is increasingly seen as proof that these projects did not optimize for carbon sequestration at the expense of biodiversity. The natural next step is moving from “quantified” to “unitized” biodiversity outcomes. This is where stacking and explicit bundling come in.

Standalone voluntary biodiversity market is a big opportunity

Not only is standalone VBM justified, it is also an opportunity to value nature more. We believe it can become a key lever in establishing the natural capital/nature as infrastructure framing that will lead to much larger investments in conservation, both market-based and not. CreditNature, Oxygen Conservation and The Landbanking Group with many others are some of the early pioneers in this movement.

Having said that, unless we find a way to include all ecosystem services into a single coveted “nature” credit, VCM will likely remain the leading voluntary environmental market, followed by VBM. Biodiversity is obviously more directly commercially important than carbon emissions but it does not easily lend itself to becoming a liquid tradable market. That means that other, less tradable nature finance instruments will have to grow fast as well.

End scale is in policy

As mentioned earlier, public good management is usually the job of the government. That is why for both biodiversity and carbon, compliance and government-led voluntary markets is the way to funnel most resources to nature. There is a reason why compliance biodiversity offset markets are estimated at $11.7 billion. There is also a reason why many in VCM expect the Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement to be a key driver for VCM’s growth.

We should put more emphasis on demand

It is no secret that the voluntary biodiversity credit demand is below the lofty expectations set in 2022 and 2023. Buyers need not only a clear why (among other things) but also a how. That is why it is important to run more strategic pilots together with the end buyers (e.g. similar to a project we are part of together with Volkswagen Financial Services). Policymakers such as the EU have a crucial part to play here.

How do we not overcomplicate things?

Although the value of VBM is clear, so are its downsides of market fragmentation. Are we heading toward a future where every single ecosystem service is explicitly monetized and traded? Will it be just carbon, biodiversity and water? Or will we reach the previously mentioned true nature credits?

This is important for every market participant: project developers, service providers and, of course, buyers. This is even more important for the local communities who are exploring how to use these mechanisms to conserve their lands.

We do not know the answer but believe that creating credits for every ecosystem service is counterproductive. Those services that justify a standalone market should be as aligned as possible, both on the voluntary and compliance side.

In other words:

Landowners should have only one form to fill out to see if any of these mechanisms can fund conservation.

Project developers should be able to easily sell their conservation outcomes into different nature markets.

Buyers should have clear guidance on how different credits interact and “when to buy what and why”.

Again, policymakers will play a key role in determining what that will look like.

We would like to thank all the suppliers who have shared their project and transaction data with us and have become our data partners. This analysis would not have been possible without you.

Really solid breakdown of stacking vs bundling dynamics. The insight about rePLANET controlling 76% of bundling-friendly projects is pretty telling about market concentration risks. I've seen similar consolidation patterns in early-stage enviromental markets, and it usually leads to pricing inefficiencies until more suppliers enter. The point about narrow buyer mandates makes alot of sense though - most procurement teams I've worked with struggle enough with single-credit evaluation, let alone multi-credit packages.

A great deep dive into these emerging environmental markets; the overlap between different markets is indeed a source of both risk and opportunity for various stakeholders. It will be interesting to see how policymakers across the world choose to align carbon & biodiversity in the next couple of years, and whether biodiversity credits will remain largely voluntary or transform into compliance/offset markets